High-Order Optimization on Large-Scale NN Training

Second-order or quasi-Newton methods have been regard impractical for large-scale problems, such as large neural net training. The main reason stem from attaining the Hessian and its inverse, with quadratic complexity in terms of a problem size. Specifically, for a neural net with $d$ parameters to be optimized, obtaining the Hessian and its inverse incurs $O(d^2)$ computation and memory complexity. Considering current deep learning models with millions of parameters, it seems impossible to apply high-order methods during optimization.

Along this line of research, we aim to design a second-order optimizer with linear complexity, and convey the promises of second-order methods to real DNN optimization.

Paper Link –

OpenReview —

Code

Overview

In this project, we delve into one widely known quasi-Newton method called L-BFGS, and convey it to current large-scale NN optimization. L-BFGS, though can converge in a super-linear rate with proper step searching, it faces severe convergence instability issues in stochastic settings. Current works that adapt L-BFGS in stochastic learning usually incurs significant additional costs, which goes against the objective of reducing complexity of quasi-Newton methods.

In this project, we propose a new momentum-based mechanism to stabilize L-BFGS in stochastic settings. Like the momentum in SGD, the momentum-based L-BFGS in almost cost-free but still capture second-order information to speed up the convergence. We evaluate momentum-based L-BFGS on common benchmark datasets (including ImageNet) and models. Experiments shows momentum-based L-BFGS enjoys much faster wall-clock convergence rate compared to other quasi-Newton methods.

Second-order Optimization

In a typical optimization problem, the objective function is usually written as

[ L(\theta;x) = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N l(\theta; x^i) ]

where $\theta$ are the parameters to be optimized, $x$ denotes the dataset.

With the Hessian or its approximation, we usually have the update as

[ \theta_{t+1} = \theta_t - \eta \cdot H \cdot g_t ]

where $H$ denotes the Hessian inverse, $g_t$ denotes the gradients.

With good estimate of the Hessian, the above optimization can be much faster than SGD. However, computing the Hessian and its inverse have been considered impractical for large-scale model training.

Where to Add Momentum

The key of using L-BFGS in stochastic optimization is to collect good pairs of gradient and parameter changes, and use these changes to compute an accurate and stable Hessian approximation.

When using the standard L-BFGS, we compute gradient and parameter changes as

[ \Delta\theta = \theta_{t} - \theta_{t-1} ]

[ \Delta g = g_t - g_{t-1} ]

However, in stochastic training, such a naive way can introduce significant noise, leading to an unstable estimation of the Hessian.

We choose a clever but lightweight way: we first compute a momentum of parameters and gradients as

[ M_{\theta} = \beta\cdot M_{\theta_{t-1}} + (1-\beta)\cdot\theta_t ]

[ M_g = \beta\cdot M_{g_{t-1}} + (1-\beta)\cdot g_t ]

Then we compute parameter and gradient changes as

[ \Delta\theta = M_{\theta_t} - M_{\theta_{t’}} ]

[ \Delta g = M_{g_t} - M_{g_{t’}} ]

With momentum, we can avoid using computation-intensive operations to stabilize the Hessian approximation. And, as we analyzed in the paper, the momentum-based L-FBGS can lead to the same Hessian approximation as the standard L-BFGS.

A Toy Example

Figure below shows a toy example on quadratic objective function. We simulate stochastic noise using a Normal distribution. We can easily see that with momentum, the optimization of L-BFGS is greatly stabilized and achieves almost the same speed as the exact Newton method. Therefore, it shows great potentials of using momentum in the Hessian approximation.

Evaluations on Real NNs

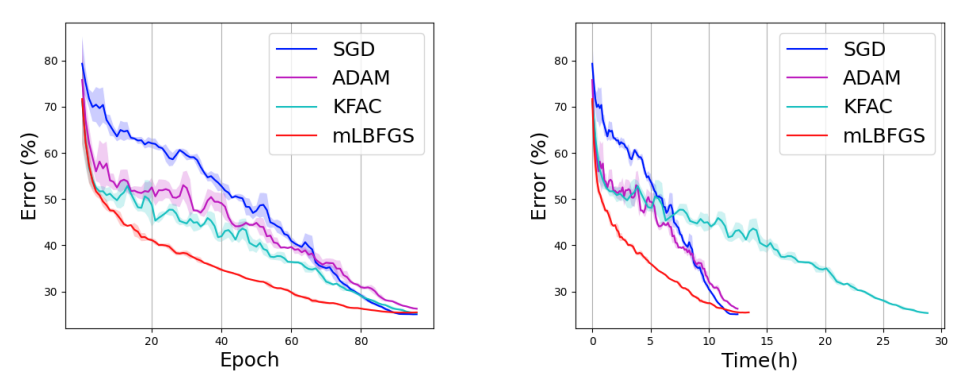

mL-BFGS not only works on simple objective functions, but also on large-scale model training. Figure below shows the per-iteration and wall-clock convergence on ResNet-50 on ImageNet.

We can easily observe that mL-BFGS has a faster convergence than SGD. And importantly delivers much better wall-clock timing performance.

More Analysis

We also have extensive theoretical convergence analyses in the paper. If you are interested, please check it out.