Differential Privacy: Basic Concepts

Differential Privacy (DP) provides a formal privacy framework that helps analyze privacy leakage for a system. However, as a beginner in privacy-related fields, we found it difficult to understand even basic concepts in DP. For instance,

- How to understand neighboring datasets?

- How to understand the DP definition itself?

It is, however, crucial to have a clear understanding of DP before developing or adapting our own privacy protection solutions. This blog provides a thorough but easy-to-follow description of the basic concepts of DP.

Understanding Basic DP concepts

A General Description of DP

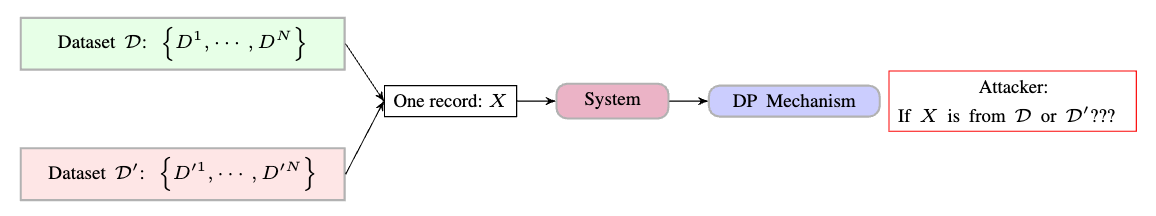

Given a system with input $X$, as shown in Figure above, a DP mechanism introduces certain randomness to the system’s output, so the input-output mapping is no longer deterministic. As a result, the outputs are non-deterministic regardless of what the inputs are.

The essence of differential privacy (DP) is to provide a metric that measures how possible an attacker can tell which dataset a data record comes from, as shown in Figure above.

It does not reflect how much information about $X$ is leaked from a system’s output, which might be why many beginners with information background find DP not intuitive.

Some typical questions may arise:

-

Will it be easier to define in a way that measures information leakage about $X$ from the system’s output?

However, such a definition is conceptually intuitive (in terms of information), but not realistic in practice. The reason is that it is impossible to know the distribution of $X$ and the system’s output in real problems. We cannot provide a formal privacy analysis if we do not know the distributions. DP is not intuitive at first glance but is more viable in terms of theoretical analysis.

-

Is it good enough to measure privacy leakage using DP?

The answer to the question is not straightforward. First, it seems not a big deal if an attacker knows if a single data record comes from the target dataset, as it does not indicate the attacker knows every record of the whole target dataset. However, assuming the attacker has many ways to pull a large number of samples from the Internet or other public sources, it can feed every collected record to the system and infer if some record exists in the target dataset. As a result, the attacker may retrieve quite a few data records from the target dataset if the target dataset also has some similar records.

Basic Concepts: Neighboring Datasets and Sensitivity

The concept of neighboring datasets is another challenge that makes DP hard to digest. Essentially, DP aims to guarantee that an attacker cannot differentiate between two close datasets. However, it is a little subtle to quantify how close the datasets are. If we look into dataset [ D: { D^1, \cdots, D^i, \cdots, D^N } \quad \text{and} \quad D’: { D’^1, \cdots, D’^i, \cdots, D’^N } ]

each dataset has multiple records, and each record can represent images, tables or other attributes. It is not straightforward to measure the closeness of $D$ and $D’$.

The way that DP deal with the closeness is to define so-called neighboring datasets $D$ and $D’$ such that $D$ and $D’$ are almost identical except one record (e.g., $D^i$ and $D’^i$) is different. This definition is also where the differential comes from.

But it is not good yet with only the neighboring datasets. We still need to formally quantify how different $D$ and $D’$ are. Given only $D^i$ and $D’^i$ are different, it becomes easier to measure the difference as we can use a certain distance measure to compute the difference, so-called sensitivity in DP. Sensitivity can be defined in multiple ways, depending on what DP mechanism is used, which will be covered in later sections.

Defining DP

We first formally describe two standard DP definitions and then provide some insights into the reasoning behind the definitions.

Def1 $(\epsilon)$-DP: A randomized mechanism $M: D \rightarrow R$ is $(\epsilon)$-DP if for any neighboring record $D$, $D’$ and $S\in R$,

[ P(M(D)\in S) \leq e^{\epsilon} \cdot P(M(D’)\in S) ]

Def2 $(\epsilon,\delta)$-DP: A randomized mechanism $M: D \rightarrow R$ is $(\epsilon,\delta)$-DP if for any neighboring record $D$, $D’$ and $S\in R$,

[ P(M(D)\in S) \leq e^{\epsilon} \cdot P(M(D’)\in S) + \delta ]

Intuitively, the two definitions above make sense as they aim to upper bound the probability difference between the outputs of two different inputs. However, they have more to say:

-

Why only provide the upper bound?

Considering the case that

[ P(M(D)\in S) = 0 \quad \text{and} \quad P(M(D’)\in S) = 1 ]

It seems still satisfy both definitions. But it would be very strange to think it is DP. So it seems not only is the upper bound needed, but also the lower bound. Answering this question needs more understanding of the DP definition. The definition states any neighboring records need to satisfy the inequality condition. As a result, if we can switch the position of $D$ and $D’$, the inequality still holds. Therefore, Definitions above also implicitly specify the lower bounds.

-

What is the difference between these two definitions?

If we define a probability distance measure $L = | \log \frac{P(M(D)\in S)}{P(M(D’)\in S)} |$, we can see $(\epsilon)$-DP always requires $L\leq \epsilon$. Namely, the two probabilities should always be close enough by $\epsilon$.

For $(\epsilon, \delta)$-DP, it does not guarantee the two probabilities are always to close enough. Suppose in a case where

[ P(M(D’)\in S) \rightarrow 0 ]

for $(\epsilon)$-DP, $P(M(D)\in S)$ is also required to be close to 0.

However, for $(\epsilon, \delta)$-DP, $P(M(D)\in S)$ can be at most $\delta$. Hence, this indicates $(\epsilon, \delta)$-DP only requires the two probabilities are close enough with probability $1-\delta$.

This short overview describe the essence of differential privacy. You can also find my blog on standard mechanism here: Laplacian Mechanism and Gaussian Mechanism